HUDSON, North Carolina – Honeybees forage their nutrition from two key plant sources: nectar and pollen. And while nectar is important, it’s the quality of pollen that is linked to colony health and growth, and may be the key to managing some of the major pollinator health issues like varroa mites and Colony Collapse Disorder.

North Carolina beekeeper Ryan Higgs embarked on a two-year project to identify the pollen his honeybees were bringing back to the hives to help connect better food sources in the natural environment to the 1,000 hives he manages.

The task was trickier than he thought, and the outcomes were not what he expected.

“Nutrition is not uniform across the spectrum. Different floral sources produce pollen with a range of protein levels. For example, buckwheat pollen has 12 percent protein; canola is in the 25 percent range depending on variety. Corn is a notoriously poor pollen source,” said Higgs, who owns and operates Blue Ridge Apiaries with his wife Launi. “If beekeepers can identify floral sources with high protein content, that’ll be healthier for the hive. Bees will be making less trips than they would be making to a more inferior food source if they had access to higher quality floral choices.”

Higgs received a Southern Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SSARE) Producer Grant to identify pollen in-house, comparing the identification process with palynologist Sophie Warny at Louisiana State University. A palynologist is someone who studies plant pollen and spores in both living and fossil form.

“Our project researched the viability of an in-house pollen identification lab to identify pollen in real time. Such analysis would provide beekeepers with valuable data to make correlations between various pollens and colony health, quick enough that management strategies could be refined or changed,” said Higgs. “Can a beekeeper reliably and accurately identify pollen sources? That’s what I aimed to find out.”

Over a two-year period, Higgs collected 29 pollen samples via the existing pollen traps from 24 honeybee colonies from three different locations. He then divided the samples into two identical groups, keeping one sample in-house and sending the other off to Warny for identification.

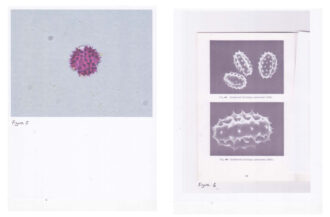

For his in-house samples, Higgs recorded the location, harvest date and pollen color, then used a compound microscope to record the details of the pollen, such as size and shape, as a 2-D image. He then attempted to identify the floral source of the pollen using a variety of reference manuals. Warny conducted a similar identification method using the same type of microscope, but then also had all the samples undergo a chemical treatment to extract additional structural details.

The two compared their results.

Higgs said trying to identify the pollen on his own farm was trickier than he anticipated. He was unable to confidently identify pollen on color alone, as many floral sources express the same color, and Higgs found more than one floral source in a pollen pellet.

“The bees were collecting pollen from more than one source during their foraging trips and putting them all together in their pollen basket,” said Higgs. “Based on the shapes of the pollen alone in the sample slides, it was evident that more than one pollen source was present, which means that bee pellets are not always as homogenous as one may assume.”

The other problem Higgs ran into was using a 2-D image to identify the pollen based on shape. “You are looking at a three-dimensional object in a 2-D format,” said Higgs. “As Warny described it, ‘pollen is seen in 2-D on slides in a variety of positions that can be confusing if you don’t have the 3-D image in your brain’.” One example Higgs gave was goldenrod, whose 2-D image looks nothing like its 3-D counterpart.

The biggest issue was extracting enough detail from the slide samples to accurately identify pollen. Warny’s samples were sent off to a lab in Canada to undergo acetolysis, a chemical treatment that breaks down the cell walls and reveals greater detail of the cell structure to help in identification.

“We had samples of what may or may not have been blackberry and locust,” said Higgs. “Without undergoing acetolysis, there’s just not enough detail available to know with any certainty.”

In some cases, pollen couldn’t be definitively identified using any of the methods. Of the samples collected, Higgs estimates that well over 100 pollen sources were available. Roughly 5 percent were unidentified. Higgs said that with thousands of plants available and a honeybee’s indiscriminate foraging habits, it really is difficult, if not impossible, for a beekeeper to accurately identify every pollen source collected.

Through the study, Higgs did receive useful data on pollen counts from sources that were accurately identified. He found the information surprising based on his knowledge of his bees’ forage habits.

“The predominance of locust, making up 43 percent of the pollen count, was a surprise. This is not a location that I have thought there would be many black locust trees,” said Higgs.

Maple came in second with 18 percent of the pollen count. “Red maple generally begins blooming the first week of February at this location, so it is interesting that in April there is still a significant amount of maple available,” said Higgs.

Blackberry represented 16 percent of the pollen count. “The blackberry bloom I usually associate with the nectar flow occurs at this location in late April, yet bees were foraging for the pollen three weeks prior.”

Higgs said that the information may be helpful for pollinator conservation and providing more diverse food sources for honeybees.

Blue Ridge Apiaries operates 1,000 honeybee hives across seven locations in the mountains of western North Carolina. Higgs is a 4th generation beekeeper, who started his commercial business in 2008.

Published by the Southern Region of the Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) program. Funded by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), Southern SARE operates under cooperative agreements with the University of Georgia, Fort Valley State University, and the Kerr Center for Sustainable Agriculture to offer competitive grants to advance sustainable agriculture in America's Southern region. This material is based upon work that is supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, through Southern Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education, under sub-award number: FS19-313. USDA is an equal opportunity employer and service provider. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.