An Integrated Systems Research Model

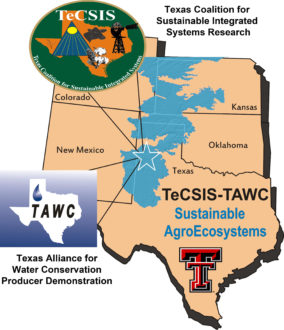

For over 20 years, Southern Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education (SSARE) has funded nearly $1.5 million in grants to Texas Tech University, Texas Coalition for Sustainable Integrated Systems (TeCSIS), Texas Alliance for Water Conservation (TAWC), and their many partners to develop alternative production systems to monoculture cotton that address the growing need for water conservation, while keeping soils fertile, crop yields profitable, cattle production thriving, and surrounding communities viable in the Texas High Plains.

This systems research effort showcases the results of long-term crop/livestock production systems, and how those results are being translated into practical field production practices and sustainable agriculture applications. This model of sustainable agroecosystems in the Texas High Plains is changing the face of agriculture in the region and helping to conserve water, improve soil health, boost ag profits and keep the High Plains region thriving for generations to come.

Sustainable High Plains Research Bulletins | Video: The Ogallala Aquifer of the Texas High Plains | Video: Water Conservation on the High Plains | Texas Water Conservation Photos

Addressing Critical Water Issues on the High Plains

The goal of U.S. agriculture is food and fiber security and an economically viable production system that does not deplete resources nor diminish the environment upon which this depends. Increasingly, agriculture is called on to provide additional services including clean air and water, wildlife habitat, recreational opportunities, and landscape aesthetics, while agriculture is also blamed for using inordinate amounts of fresh water for irrigation. Agriculture uses 61 percent of the total U.S. withdrawals of fresh water (excluding that used for power plant cooling, https://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1405/), and uses 95 percent of groundwater withdrawals in the Texas High Plains (https://www.twdb.texas.gov/).

To meet these challenges, knowledge of the functioning of agricultural ecosystems is essential. Such knowledge must be derived from long-term, systems-level research that leads to understanding interrelationships of basic biophysical processes, human needs and manipulation of the system, and impacts of policies, economics, and market forces.

The Texas High Plains serves as a model region when studying factors affecting agricultural sustainability, especially for the efficient use of water and protective management of soil.

Texas High Plains and the Ogallala Aquifer

The Texas High Plains is a large swath of area, roughly 22 million acres, in the Texas Panhandle that historically was a nearly level, treeless, semiarid grassland. In the early decades of the 1900s, with the advent of rural electrification and pumping technology, tapping into the Ogallala Aquifer for irrigation made row crop cultivation, mainly cotton, possible. Today, roughly 25 percent of the total U.S. cotton crop is produced in this region. In addition, the High Plains serves as a grazing resource for stocker cattle before they enter feedlots. Wheat, alfalfa, warm-season grasses and other forages have served as feed for decades.

In the Texas High Plains, an area that receives only 18 inches of rainfall annually in an average year, the Ogallala Aquifer is a crucial, but finite resource. The Ogallala was formed millions of years ago from the erosion of the Rocky Mountains and now traverses through portions of eight states—Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas and Wyoming—providing 30 percent of the United States’ irrigation, and contributing to an astounding 20 percent of the country’s entire agricultural output. As droughts across the Texas Panhandle increase, intensify and endure, it is quickly becoming clear that the increasing number of irrigation wells, and lack of adequate recharge from more northern states, is bringing High Plains agriculture to a crisis point. Studies have indicated that water levels in the Ogallala are dropping at an alarming rate, with some studies estimating the aquifer will run dry in just 50 years time. In this semi-arid region, agriculture accounts for over 40 percent of the economy, including support of numerous rural communities, but depends heavily on irrigation from the Ogallala Aquifer at non-sustainable withdrawal rates. Recharge is negligible and well output is dropping to the point that farmers are having to adopt new systems to maintain profitable survival of their businesses and the communities that depend on their economic activity.

Sustainable Agroecosystems in the Texas High Plains

The importance of crops, forages, and livestock to the Texas High Plains has highlighted the need to develop systems that enhance profitability, improve conservation of soil and water resources, and expand marketing opportunities for a more sustainable agricultural system. In the late 1990s, a committed and dedicated team of researchers from Texas Tech University in Lubbock, TX took one of the first steps to begin exploring a systems approach to implement agricultural production alternatives that use less water. Researchers received a Southern Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education (SSARE) grant to jump start those efforts.

The research conducted at the Texas Tech University New Deal Research Farm covers the use of grazing systems with beef cattle that, when integrated into farming systems involving annual crops, can reduce inputs of irrigation water, fertilizers, and pesticides, while building up soil organic matter and microbial diversity. The impetus for this research is the declining supply of groundwater from the Ogallala Aquifer used in large scale, row-crop farming, and therefore, the need for systems that use less water while building soil quality and maintaining profitability.

Cropping choices by producers largely follow crop prices and input costs and can lead to excessive water use, but limited cropping of strategically irrigated crops and a perennial grass grazing-based beef industry could be sustained indefinitely. To be sustainable, such systems must also be energy efficient and economically viable. This project has supported infrastructure for conducting research on overall water use of integrated crop and livestock systems as well as forage systems.

Results feed directly into a current outreach program (Texas Alliance for Water Conservation) and offer answers on how to reallocate diminishing irrigation water to annual row crops and forage systems to maximize economic returns.

The premise is that there are novel methods of managing forages which are as climate-resilient as native grasslands but more economically productive, and which entail user-friendly technologies for monitoring use of water and making economic decisions. Systems based on or inclusive of forages and livestock require less water for irrigation and livestock use than systems based entirely on row crops. How the system is configured, the forage species used, and the timing of grazing all impact total water required and economic profitability.

The Future of High Plains Agriculture

The research has created a greater awareness of the need for water conservation across the Texas High Plains. Producers are moving toward a more integrated strategy to match water with fertility to target realistic yield goals rather than maximum production.

In the context of transitioning to low-irrigation management, Texas Tech University researchers foresee the following trends in Texas High Plains Agriculture in the coming decades:

- Smaller acreages of irrigation of value-added crops;

- Continual improvements in water use efficiency of major row crops such as cotton;

- Partial replacement of irrigated row crops with perennial grasses and legumes and with dryland crops, especially sorghum;

- Greater use of precision water management technologies such as ultra-low and variable-rate irrigation;

- Greater dependence on online decision aides for guiding inputs;

- Warmer temperatures leading to greater evaporative demand and more droughts.

These trends require constant testing of forage systems across the range of weather conditions experienced to offer options to landowners on how to maintain profitability. Researchers continue to seek ways to conserve, cooperate, educate and strive to continue to solve the ever pressing issues of sustainability and the challenges to agriculture in the High Plains region.

Answers derived from this and other research have implications far beyond the Texas High Plains and will help to provide answers to sustaining ag productivity while minimizing negative impacts on our natural resources.

Published by the Southern Region of the Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) program. Funded by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), Southern SARE operates under cooperative agreements with the University of Georgia, Fort Valley State University, and the Kerr Center for Sustainable Agriculture to offer competitive grants to advance sustainable agriculture in America's Southern region. This material is based upon work that is supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, through Southern Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education, under sub-award numbers: LS97-082, LS02-131, LS08-202, LS10-229, LS11-238, LS14-261, LS17-286, GS02-012, GS07-056, GS15-152 and GS18-196. USDA is an equal opportunity employer and service provider. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.